目次

Introduction

This program aims to convey the appeal of Central and Eastern European art and culture by inviting experts from each country to give lectures.

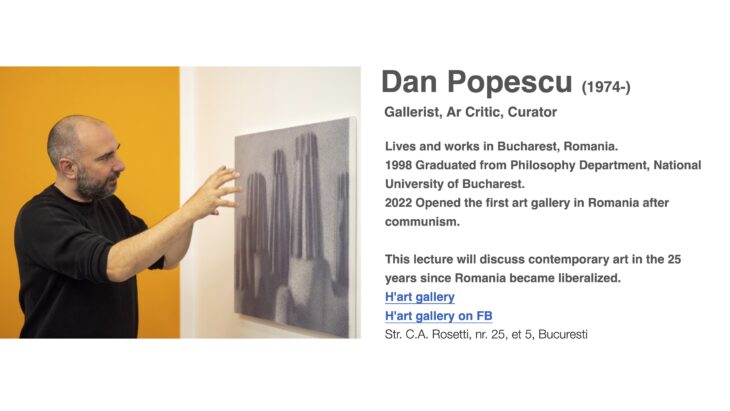

This time, we invited H’art Gallery, which opened Romania’s first contemporary art gallery 21 years ago in the Romanian capital, Bucharest.

Romania is the eastern EU member states in Europe, and has always had a tumultuous history of religious conflicts and territorial disputes throughout its long continental European history.

The country is a complex mixture of cultures and languages of Slavic peoples from the Czech Republic to around Russia, Latin peoples from Italy and France, and Balkan peoples from Turkey.

In this land where “ethnicity, borders, language, and religion” have changed dramatically over the centuries. Dan Popescu, an art historian, curator, and gallerist, gave us a three-hour talk on the “Romanian modern and contemporary art specificities”.

The following is a summary of Mr. Popescu’s presentation.

Characteristics of Art in Romania

Now I would like to talk about the character and characteristics of Romanian modern and contemporary art.

First of all, it is important to ask what is the main power and motivation of Romanian art. In this regard, we would like to talk about two major characteristics, although they are very brief.

1: Sensitivity to tradition and ceremony, and the influence of folk art and contemporary nostalgic expressions

2: Humor in the context of historical factors (especially the pressures of occupation).

Today I would like to talk about these issues as clearly as possible, without fear of risks or mistakes, although it is not easy.

History and Peculiarities of Romania

First of all, the peculiar thing to know about Romania is that “it has never been an empire” compared to other European countries. Secondly, Romania became a “country” only after the First World War, it may be only recently.

Even countries and ethnic groups are subdivided, and Romania, for example, has such a wide variety of cultures, variety and taste that there are 136 different types of traditional clothing.

Broadly speaking, Romania can be divided into three regions. The southern area, which has been in three separate empires, the Transylvanian region in the north, and the Moldovan region in the east. The Moldovan region was formerly under the Russian Empire, the southern area under the Turkish Empire, and the west under the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was combined into one and became Romania after the World War. The basic mindset of the people who were invaded by the three empires was a disposition to develop their own way to go against those oppressions. It was a unique and different way, ironic and humorous, but also a way to carry on their traditions.

How Romania reconciled its geopolitically divided world with its original unique and diverse differences to create a unified self-identity was part of its history and influenced its artists.

In this sense, the Romanian “influence and expression of tradition and folk art” and “humor” mentioned at the beginning of this article come from an experiential history.

Constantin Brancusi

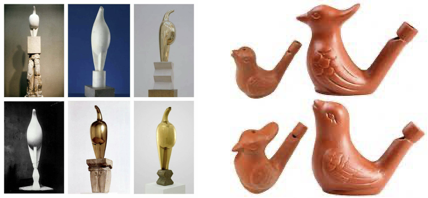

Let us begin by looking at Constantin Brancusi (1976-1957) as an example of a national artist. He is a Romanian who developed his talent in Paris, France. One of his most famous works is “The Endless Column” (Infinity Column).

This was a time when Braque, Picasso, and others often applied to art what they had been inspired by in African folk art. Brancusi, however, sought this not in Africa but in his own tradition.

In the early 20th century, the indigenous rural architectural style of his native Orthenia had many columns like Brancusi’s columns. The idea for “The Endless Column” was inspired by the columns common in his rural style.

Even in the sense of a pillar of a house, this infinity pillar is not a tower extending toward the heavens, but a “pillar supporting the heavens,” which is the opposite of the common idea of a tower leading to the heavens. Incidentally, the infinity pillar in the outdoor work shown in the photo is a unit about the same size as an average person, with a device that makes people think they can climb the pillar, a metaphor crossed with a person, and other thoughts.

Next, Brancusi’s famous series of sculptures of birds was inspired by the ceramic and wooden flutes known in his countryside, which he used to call his sheep and other livestock.

Thus, quotations from traditional Romanian crafts and craftsmanship underpin his celebrated work.

As ISAMU NOGUCHI, born of Japanese and American descent, explored the roots of his aesthetic sense by designing a lantern lamp out of a lantern ghost, “Best artists are influenced by own native tradition”.

Artists’ Union

By the way, why is the history of the Romanian art market so young?

One of the main reasons is that Romania was a communist country between 1945 and 1989. The concept of individuals buying art for their own taste, as in today’s free economy, was almost non-existent. Furthermore, even after the revolution of 1989, its communist institutions and its system continued to function until about 1999.

The only main institution governing the arts was the communist-controlled “Artists’ Union,” which was created in 1945 by a Soviet agency. The Artists’ Union was created in 1945 by a Soviet agency, and although the assets and property belonged to the government, artists could receive support from the government.

For example, when a student graduates from an art college, he or she is eligible to become a member of an art union. Although there are no cash benefits, students who belong to this union are provided with a studio to work in and materials for their artwork. In addition, students are given travel expenses for study in Italy for example, or summer camps, and other opportunities. In addition, some artists were able to borrow money from the “Communist Bank” and repay it with their works.

This had the advantage of belonging to the government, but at the same time, the artists were subject to government audits of their work to ensure that they were not doing anything that went against the wishes of the government. At times, artists were asked to produce works that could be used for socialist or war propaganda.

With the Revolution of 1989, all of these systems came to an end, and artists had to pay higher studio fees and materials, and it became difficult to obtain visas to travel abroad, making it impossible for artists who had benefited from government assistance to make a living.

H’art Gallery

H’art Gallery opened in 2002, after the country had liberalized and settled down. It is the first private, self-managed contemporary art gallery in Romania.

Up until 2002, when I opened my gallery, the world was in a state of great turmoil, and artists were simply at the mercy of this turmoil. However, since 2002, the art market seems to have been somewhat established. Buildings and their tenants are no longer managed as they used to be, and they have become untouched and abandoned. The concept of “exhibiting artwork” was not what it is today, and the only place to start an exhibition was at the site of a wildly abandoned store. The current generation of artists in their 40s and older, who lived through such a period, have come to believe that if there is no good space, they should create a painting or an object that would surpass or destroy it. In this way, Romanian artists developed the ability to adapt to any social situation.

In the days of the “Artists’ union”, only artists who belonged to the union were “artists,” but from now on, “artists who can freely work in society artists”.

Now, I would like to show more specifically the trend of Romanian art, using some of the gallery artists as examples.

>List of Art University & Art Academy in Central and Eastern Europe

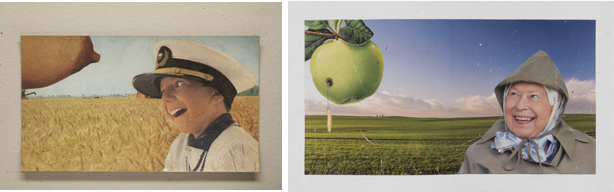

Dumitru Gorzo

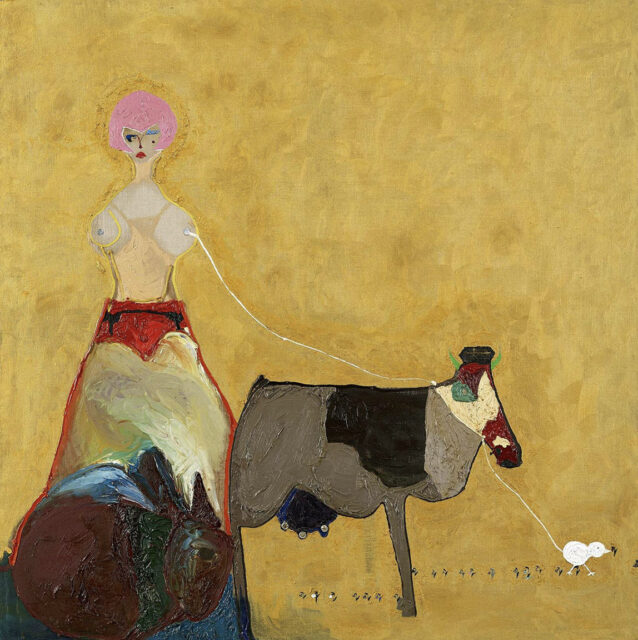

Let’s start it from Dumitru Gorzo 1975-), he is from Bucharest, and very well respected both in Romania and abroad.

Scandalizing and breaking taboos can be seen in his expression, He uses concepts of criticism and irony against authority, and powerfully confronts deep-seated social taboos, yet digests them as comical art expressions.

He also comes from Maramures, which is famous for its woodworking folk art, a technique he incorporates into his production identity.

In the four women in the photo, He carves a large wooden slab and develops an exploration of sexuality.

The humor is humorous, with his own head on a plate, genitals, breasts, and costumes in a messy state of disarray, fitting the title of the work, “Chick and Dick”. The patterns on the backgrounds of the women are patterned after the embroidery designs of his hometown. At the time this work was created in 2003, publicly revealing one’s sexual identity like this would have been a huge shock to society.

The next project was a public outside painting near a university in Bucharest. It was a painting of rural people on a wall in the city center, and the people of Bucharest saw this and proceeded to paint pranks on it. But for him, he said, “No matter what anyone paints, the wall will be better because this painting itself is strong.” In other words, for a generation like his, who went through a difficult transitional period in Romania’s social situation, he has the courage to paint something so strong and the bull to accept the situation. Incidentally, he exhibited this wall in a substandard and smart way by cutting it out and bringing it to the gallery.

He also did a similar project in Germany, and it is impressive that no one in Germany ever overwrote his wall. Germany is rule-oriented, while Romania is punk anarchy. The Romanian characteristic of messing everything up and covering it up is exposed.

Last but not least is the “COCOONS” project, which caused a scandal after it was announced. He attached hundreds of pink “cocoon” objects made of plaster to public buildings and walls without permission.

At the time this was done in 2003, the illegal “graffiti culture” did not exist in Romania, and there was no concept or information about it. In this sense, he may be a pioneer.

We tried to experiment with the idea of making the outside or a public space like an interior space for artists, and conversely, we hypothesized that the perception, functionality, and perspective of things that were inside the gallery space would change if they were outside.

People began to gossip about various things. Some people thought it was a media advertisement for birth control because it looked like a small baby wrapped in a baby blanket. Others thought it was a sign of an earthquake, done by the government. Others said it was pornographic, a symbol of Satanism, hypnosis, and brainwashing. Some people tried to remove this object, but since it was firmly attached to the wall and could not be removed without smashing it with a hammer, they thought it might be a bee sting. Some people refused to take it off because they thought it would be a bee sting.

Then, to our surprise, it was featured for 4 minutes on Romanian TV and Prime time TV news. Normally, a four-minute feature on contemporary art would not be possible.

The program even rumored that “Satan has come to Bucharest” and “the Secret Service has done it.

The social situation in Romania in 2003 was very different from today. These activities were new, no one knew what to do about them, and there were no laws or penalties against them.

It may be difficult for Japanese to imagine, but the history of Romania and Europe has been cut into different segments of the world in the last 100 years alone. Therefore, the “present” is strongly viewed as a “process” from the past to the future. This perspective is the reason why activities that could be called socially “anarchic” can appear and disappear so suddenly and so easily.

Marian Zidaru

Next up are the paintings and sculptures of Marian Zidaru (1936-). He claims to have been influenced by Brancusi, and like him, she also creates many wood sculptures.

Religious and mystical, he feels there is an important connection to the sensation (texture) of the sculptural surface, with motifs of divine imagery, centaurs, and angels. The surface of the work bears the marks of direct axe carving, combining Romanian woodwork with emotional expressionism.

In the exhibition that took place in Venice, he created a scene from the Christian bible, an image of a goddess. I believe his indigenous influence is the woodworking “altars” used by the Romanian Orthodox Church, which is widespread in Romania. This woodworking technique, atmosphere and carving habits may have influenced his work.

Giuliano Nardin

Giuliano Nardin (1978- ) is a writer from the Ortenia region who expresses himself in a naive and naive way. His Romanianness has the mentality of the “Moroi” of this region, famous for Dracula and vampires.

The Moroi are a kind of being between vampires and zombies, and the people of this region believed that once a person dies, he or she can come back to life in a zombie-like manner.

As you can see in the picture on the left, the Moroi have an arrow in their hearts, but they are still alive, and they are naive, simple, and vital.

I feel Romanian art here, too, with a mind influenced by folklore fairy tales such as the Moroi, combined with subtle cartoon-like modern expressions.

His colorful color scheme is similar to that of traditional Oltenian carpets, and it is interesting to compare these with traditional Turkish techniques that have been further developed in Romania and cited by the artist.

Ion Bârlădeanu

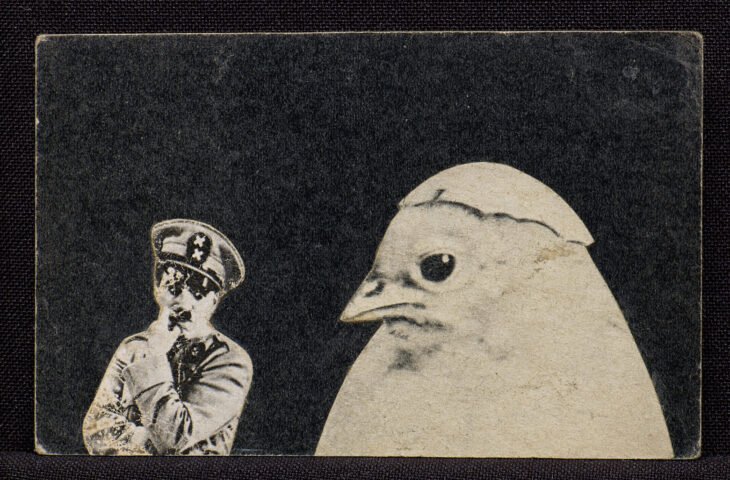

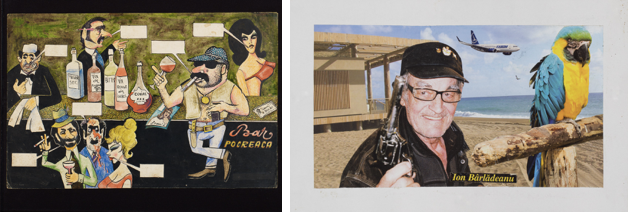

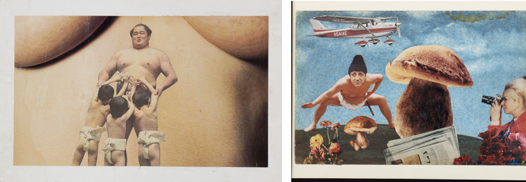

Ion Bârlădeanu (1946 – 2021) is one of the most impressive and interesting artists for me.

He was very talented and one of the most important artists in the history of contemporary art in Romania, and he died in 2021.

He has no education in art or fine arts, and his Art Brut background is an important part of his story.

He was born in 1946 in rural Romania. He left the countryside when he was 18 because he disliked his father, who worked for a communist institution. He loved to draw cartoons and spent his late teens and twenties working and drawing at night in countryside bars.

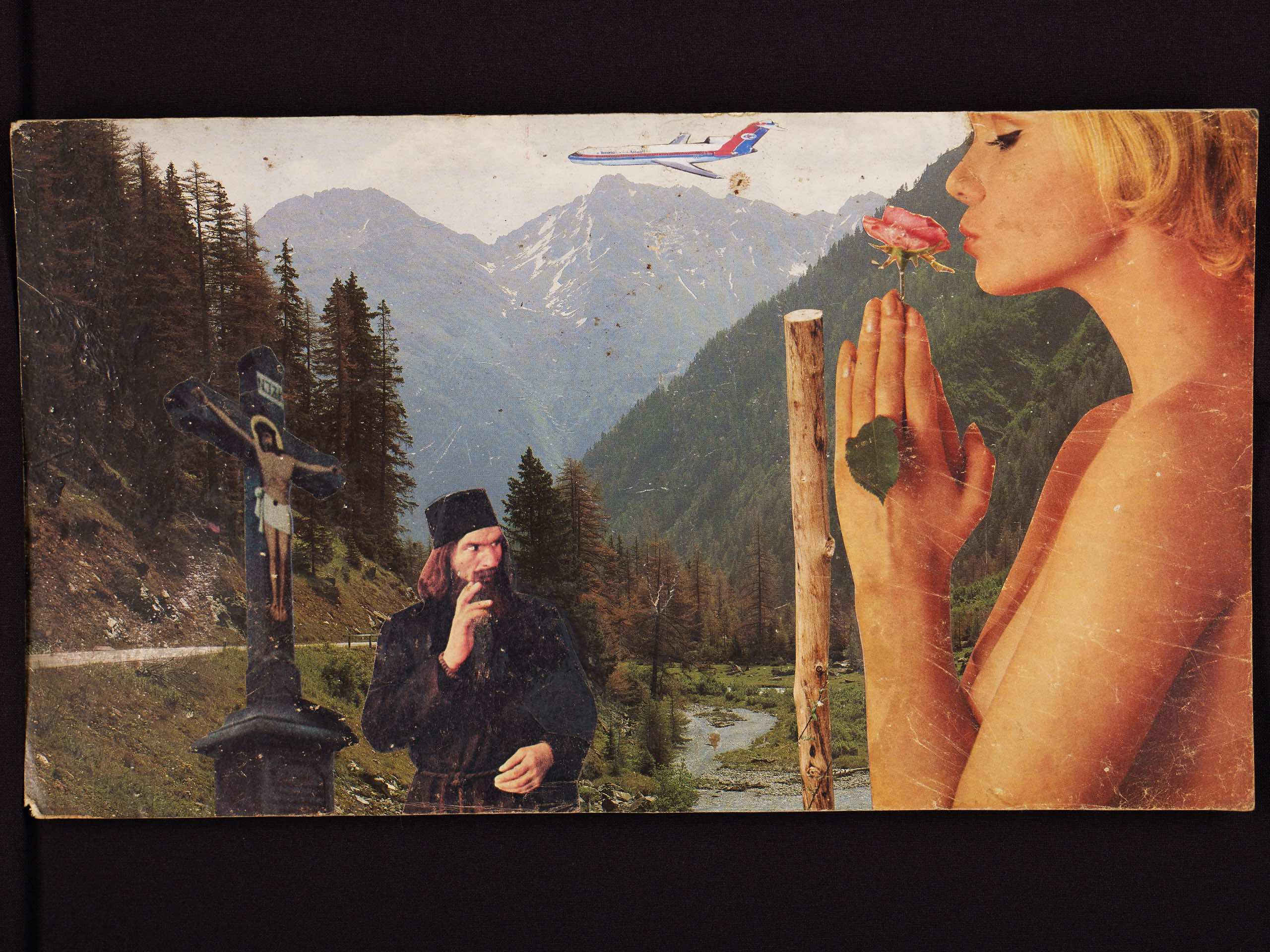

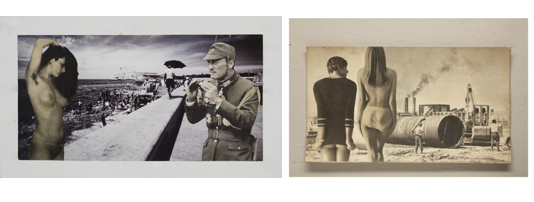

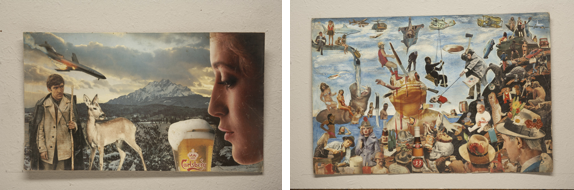

His collages began around 1980.

As a shortcut to avoid drawing and coloring, he cut and pasted magazines and newspapers. Incidentally, at that time, magazines and other materials from foreign countries were not readily available. By 1983, he says he was able to compose collages like the surrealist Dali.

He became more and more absorbed in the world of collage.

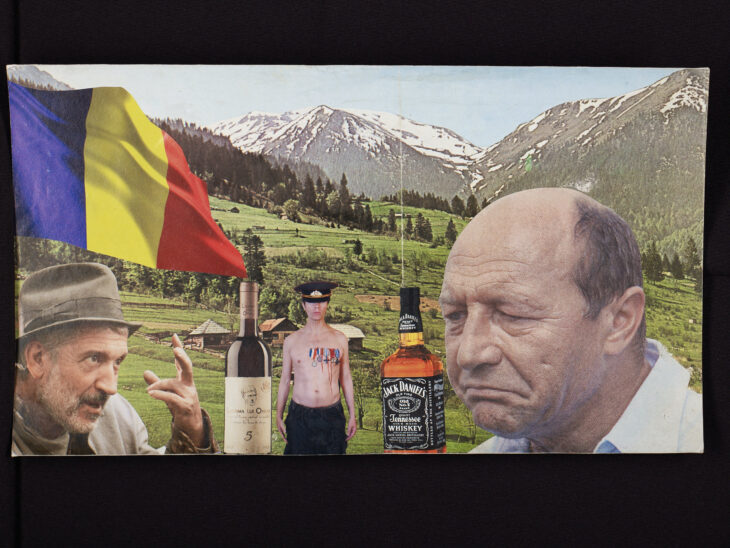

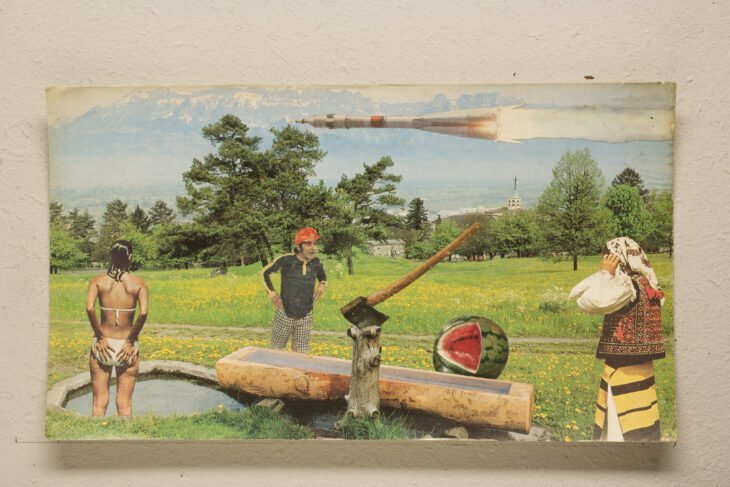

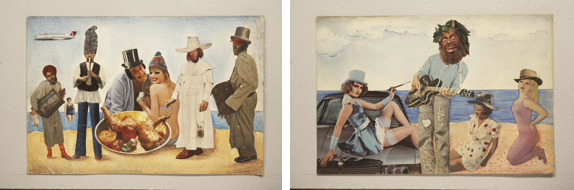

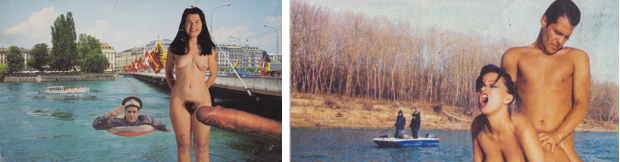

In this screen, he is free to be the filmmaker and create a scene from any story he wants. What’s more, artists and actors from Romania and around the world appeared in the film for free. Once he became a director, he went about his production with professionalism. Whether the theme was horror, political or pornographic, he passionately created a scene from a still full of humor and irony.

Now, how did he come up with his unique style?

The answer to this question can be answered: because he did not know the history of collage. After learning about the collages of Braque and Picasso, many artists imitated them, but he had no such information, which is why he was able to develop his own style.

In fact, our encounter with him began when a friend, an artist, found him in the courtyard. He was a homeless man who had been living in a dump for 12 years, having lost his job at the time of the liberalization of the city in 1989. When we met him in an alley in Bucharest, he was carrying a collage he had been making since the 1970s in a trunk he had picked up. He was an alcoholic and in no condition to make a decent living, so I bathed him, rented him an apartment, fed him, and arranged for him to make a living by selling his artwork.

During the 15 years or so that we have known each other, we have exhibited together in Romania and abroad for more than 30 years and have spent a great deal of time together. “From the trash can to the gallery”, his career has become an important place in Romanian contemporary art. This is a very important point in our history.

If I were to give the characteristics of Romania from this example, I would say that a small country like Romania that was not under an empire as a theory, or a country that is not organized with large and frequent changes of government, has a very strong sense of humor.

Everything can be a subject, and everything can be the object of humor. Because there are no rules, everything can be the subject, whether it is church or politics, and that means that there are no taboos or limits to expression, and everything can be art.

Gili Mocanu

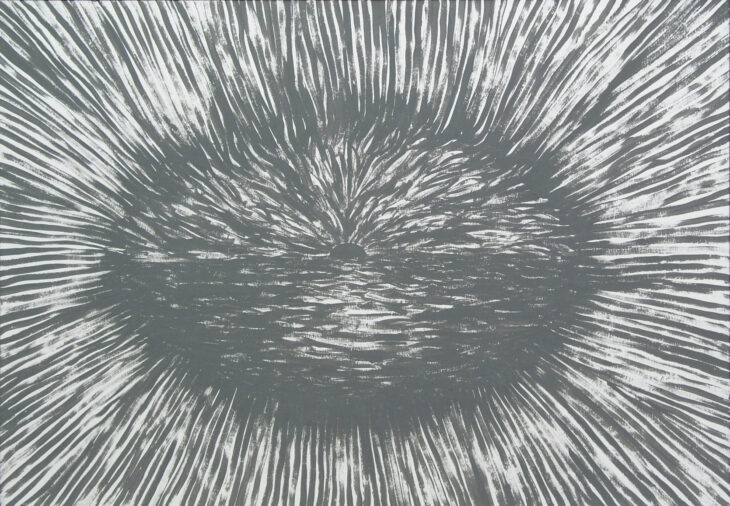

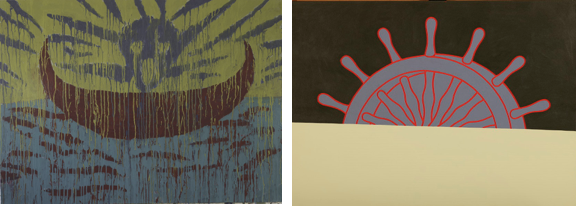

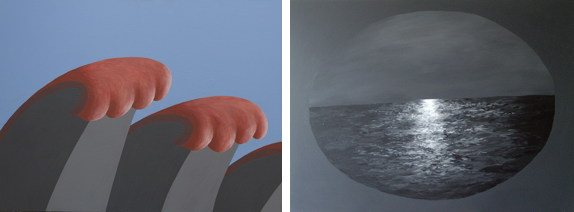

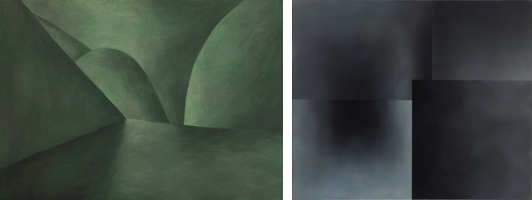

Gili Mocanu 1971-、ails from Constanta, a port city in the east of Romania. He is a painter of passionate images and adapts his own experiences to his paintings.

Titled “Sea of Death,” the work is about the sea and the experiences there, the sloshing flow of water paint and the effect of colors flowing and blending together, all of which appear more passionate.

The works are also impressive for their meaningful, multidimensional representations of metaphysical landscapes, such as quoting horizon lines and stone Hokusai waves.

In recent years, he has been showing the disappearance of the self through “Serlfportraits,” in which he interacts with things that have no form.

Modernists in American abstract painting have worked to create a flat surface of color in their paintings, and in his case, too, there is a connection with related philosophies, albeit in slightly different styles. In this kaleidoscopic work, we can see the common thread of “life is an illusion”.

Using imagery, the painting functions as a gateway to the imaginary. There seems to be some common consciousness with the Buddhist part of your work.

Victoria Zidaru

Victoria Zidaru (1965-), wife of Marian Zidaru, is an artist who sculpts and installs with primitive materials such as fabric, soil, seeds, branches, and insects. There is an approach to her own roots and invisible forces, such as spirituality and Christianity, and she also focuses on the relationship that occurs between the object and the viewer, for example, prayer and ritualistic acts.

Feminine fabrics, embroidery methods of expression, and cultural acts performed by living families in their daily lives are incorporated into the production.

Anca Mureșan

Anca Mureșan (1965-) is an artist who installs countless paintings of different sizes throughout a room.

Her photographic installations were the first to be exhibited at Hart Gallery, and from there her work has continued to evolve.

Painters who do two-dimensional art are often confronted with 3D, but Anca Mureșan rejects the three-dimensional world.

The exhibition space was entirely filled with two-dimensional objects, based on the idea that “living people share three dimensions, which means that they induce death; the two-dimensional world is something that only humans can have in their minds, and that world will live on.”

In the case of the Japanese, space and a blank sheet of paper themselves have meaning as a subject. In contrast, her way of filling the space with two-dimensional paintings and immersing the viewer in her image may be a reflection of her country’s character.

These are just some of the artists with whom I work, and I hope you have been able to sense Romanian characteristics here.

I believe that tradition and nostalgic ways of expression, anarchy, punk and ironic spirits, are alive and well in contemporary Romanian art.

Summary

This time, in the Nihon University College of Art, Art Lecture V, “Art and Society,” we were able to spend some time on the theme of “Romanian Art” in Eastern Europe, which students usually do not have a chance to learn about. We would like to thank Mr. Popescu for his lecture.

Q&A

Q1: I would like to know which Japanese artists and their works you like the most.

A1: Tets Ohnari, Ryuta Iida, Isamu Noguchi, Nobuyoshi Araki and Hiroshi Sugimoto

Q2: What do you think is necessary to develop an aesthetic sense for good artists and their work?

A2: Complete sincerity and skill

Q2: How do you see the future of Romanian art changing?

A3: It’s unpredictable. Art has a life of it’s own. You can only prepare your attention, like a hunter. Could be different technique, could be new way of approaching a subject. For example, in painting, the newest thing is that painters like Lucian Hrisav and Radu Pandele they use spray and airbrush instead of pencil or brush.