Not only have we encountered the unprecedented pandemic, but the demand for facing global environmental issues such as global warming and ecological destruction has skyrocketed in recent years.

Simultaneously, exploring the nature within our body and the connection between us and the universe has become a trend. As yoga and meditation are inarguably in mental fashion, disrepute of spirituality is already in the past. Nowadays, the demand is enlarging among not only the public but also entrepreneurs and scientists.

It is noteworthy to point out the modern trend of forming a natural and neutral sense in the body and the inner-self, re-acknowledging ourselves and everything as being linked by Engi (縁起 / also known as “paṭiccasamuppāda” in Sanskrit).

In this article, we spotlight ecology by diving into the unique Japanese perspective on nature, Jinen (自然), and its relation to art.

目次

Jinen and Shizen

Japanese term of nature [ 自然 ] has been pronounced as “Shizen” but not “Jinen” since the Meiji Restoration, Meiji-era in the end of 19century.

‘Jizen’ and ‘shizen’ are Japanese expressions with similar connotations, but there are philosophical differences.

‘Shizen’ refers to nature itself and includes natural forces, laws and phenomena. ‘Jizen’, on the other hand, reafers to the relationship between nature and humans, and includes the idea that humans are connected to nature and that it is important to value harmony and co-existence with nature. In other words, ‘shizen’ is a word that refers to nature itself, which exists objectively, while ‘jinen’ is a word that expresses the philosophical idea that it is important to understand our connection with nature and to protect it by looking at nature from a human subjective perspective.

While ‘shizen’ includes material natural phenomena and the life force of living organisms, ‘jinen’ includes the idea that it is important for humans to deepen their connection with nature and live in harmony with nature by sensing and relating to these phenomena and forces themselves.

Historical Background of Jinen

The perspective on nature in Japan underwent a drastic change due to the Westernization that started in the Meiji era (1868 — 1912). Later on, the current Japanese concept of the word “nature =Shizen” was installed by the government. Because the prior notion of nature in Japan, “Jinen,” was different from the Western concept of “nature,” meaning every tree and bush. Therefore, it was not merely the shift in the spelling of “nature,” from “Jinen” to “Shizen,” but more importantly, the whole concept of nature changed before and after the Meiji era.

So, what exactly was the original sense of Japanese perspectives on nature Jinen?

It was a complex combination of Confucianism, Shintoism, Buddhism, contemporary Western culture, and Jinen. At the basis of the concept, it understands “logics (理 / ri)” and “energy (気 / ki)” as nature, which is a kind of “Spontaneity = Onozukara-narumono.” In other words, the concept of nature embraces both earth and heaven, which has roots in the Chinese philosophy of oneness.

The difference between Buddhist studies in India and China is that the latter affirms the possibility of Buddha-nature in any natural materials. Keikei Tannen, the founder of the Tendai sect of Buddhism, mentions in his book Konpei-ron (金錍論) that each grass, wood, and even a pebble holds a Buddha-nature.

The oneness of the whole creation is mediated through the philosophy of Zhuangzi (荘子) by Zhuang Zhou. The word “Jinen” did not exist in texts from the 8th century, such as Records of Ancient Matters (古事記), The Chronicle of Japan (日本書紀), and The Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves (万葉集). Afterward, the idea of “Jinen” finally appeared in The Pillow Book (枕草子) and The Tale of Genji (源氏物語), recognizing inner nature as something operated by the universe. Hereafter, great attention was paid to nature within ourselves, treasuring “Seimei-shin,” or the innocence at heart.

Among many other types of Chinese philosophy, neo-Confucianism significantly influenced the Japanese perspective on nature in two ways. Firstly, it marginalized several philosophical perspectives on nature, namely, external, metaphysical, and internal. As for the first point, Shuki states that the ultimate existence of the universe resides within human beings and everything. Secondly, it stimulated interest in natural science.

Consequently, the Japanese perspective on nature has no distinction between humans, animals, and old-growth forests. Instead, the whole creation is connected, and so as people. Nevertheless, as stated earlier, the idea faced a problem in modernizing the nation as the conventional perspective and the Western notion collided.

Jinen in Art

Where can we find the concept of Jinen today? If the antonym of the word art is nature, would it make artists, artworks, and museums non-nature? Furthermore, what influence does the traditional Japanese perspective on nature have on today’s art? Would there be any concept as non-Jinen?

To explore these questions further, here is a selection of three artists that resonate with the Japanese perspective on nature.

Lee Ufan

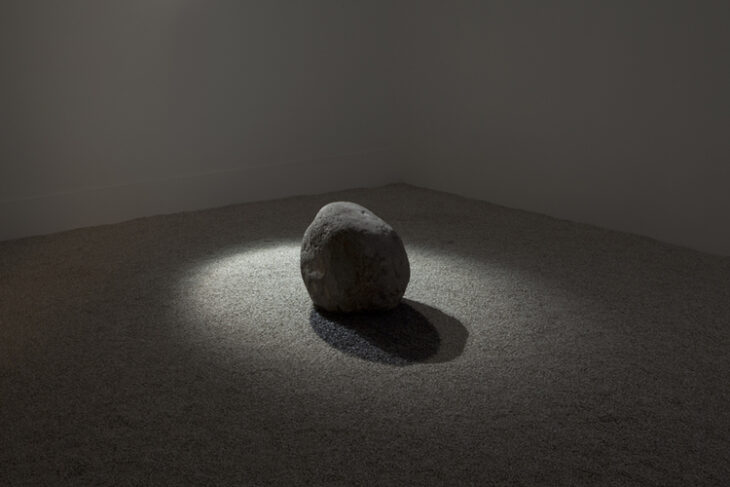

The first artist is Lee Ufan, the leading philosophical figure of the Japanese art movement after World War II called Mono-ha. The mono-ha artists explored the relationship between “things (mono)” and themselves, liberating the border between subject and object by using natural materials such as wood and stones or neutral elements such as paper and iron.

As the logical pillar of mono-ha, Lee Ufan seeks to find “an encounter with the world as it is,” resisting the Western attitude toward the creation process with the proposition of the artists’ concept. In other words, it embraces an uncreated element within artworks instead of being dominant, proactively involving and linking natural and industrial materials in his works. In his framework, there is the attitude of denying the subjectivity of artists and the objectivity of things. Underlining the concept of Jinen, there is no confrontation between humans and nature in his works, for humans are part of nature.

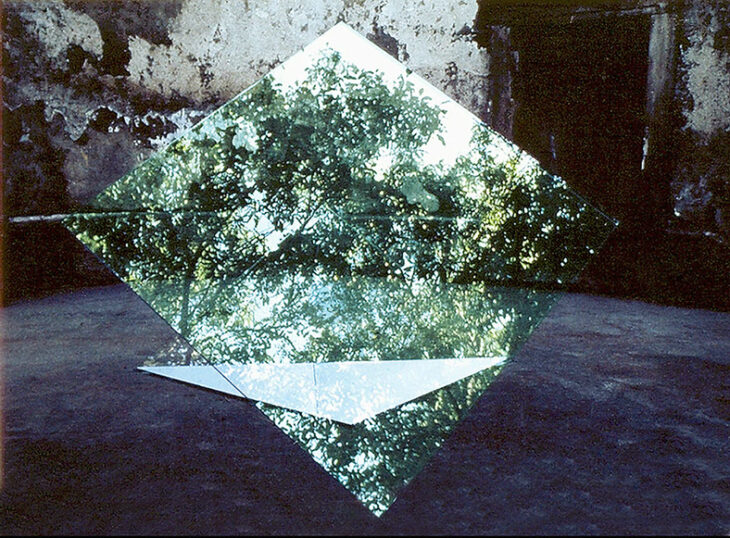

Marian Karel

The second figure is Marian Karel, a sculptor from the Czech Republic. His works are themed on the geometrical figures of glasses and the relationships between space and light, combining architectural materials such as transparent glasses, stones, and metals. By controlling the natural light, a fantastical space formed by his works melts in the environment. As a result, it creates a mirror of another world without touching the original scenery.

Tets Ohnari

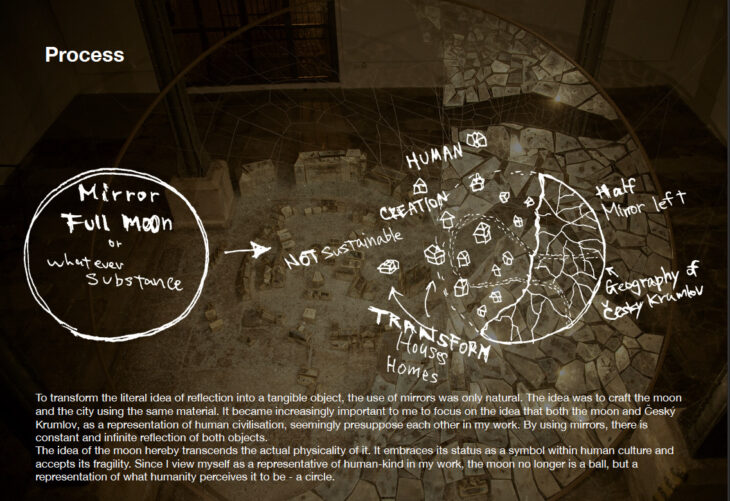

The final example is the artwork by Tets Ohnari, a Japanese sculptor based in Prague. The work is titled “.moon .mono .homo,” exhibited at Egon Schiele Art Centrum. This artwork consists of a self-made mirror, likening the houses in Český Krumlov and a 7-meter moon. Cutting out a half-moon, it leans against a pillar of the exhibition space. With the other half, 80 dwellings of the city are produced in the 1:100 scale, likening the cluster of mirror houses to crystals.

Additionally, the half-moon made of the mirror is divided into the actual configuration of the place, establishing the dual image of the city and its map. It uncovers the naturalness through the mirror and moon that tells their existence only by the reflection of lights. In this way, it recognizes the dwellings and the half-moon as a metaphor for art and nature.

Jinen to the Contemporary World

Examining the notion of Jinen, it can be regarded as essential knowledge to survive the Anthropocene. Caring for the natural environment and understanding people within nature may be a way to face a time of ongoing crisis.

A recent trend on mindfulness may be a way to calm your body and mind by resonating with nature within. The trend reflects the concept of Jinen, for it allows us to recognize ourselves as a part of nature continuously.

Although Jinen is quite a traditional notion, it echoes today’s world and artists.